A collection of reflections and rants from a sometimes angry, often snobby, dangerously irreverent, sacramental(ish), and slightly insane Baptist pastor

Monday, March 31, 2014

Listen and Question

I've just posted a new podcast episode for your listening pleasure. You can follow this link, or find the podcast through Itunes under "twelve enough" - all written out... that is important!

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

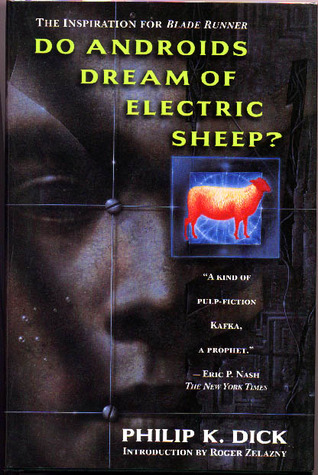

Dreaming and Living

A review/reflection of "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

It is a dangerous thing to recommend any bit of science-fiction

literature to someone who is not a fan. Bad Sci-fi is deadly and can send

anyone running to embrace the eventual onslaught of the robot overlords if they

demand that everyone only read romance novels. Even mediocre sci-fi can turn

the newbie off from the genre as it can be difficult to wrap one’s head around

the notion of aliens who actually settled the Earth eons ago and

we are the aliens. Thus one must be very careful when recommending any sci-fi

to the general public because the side effects can be deadly (those of us who

are enlightened and understand the brilliance of the genre can dive into almost

any sci-fi story and find gems among the garbage, but we are enlightened).

With all of that said, it is with no hesitation that I

recommend Philip K. Dick’s 1968 classic work Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? to the wider public. I

recommend it not so much because it creates a fantastic world that we would

aspire to live in (it instead leans towards the dark, dystopian notion of the

future), or because the poetic nature of the writing emulates Shakespeare and

Dante (it doesn’t). Dick’s writing is fine, slightly better than average, but

not brilliant. He doesn’t create a world of hope but more one of despair. I

recommend it because of the questions Dick asks, questions that are very much prevalent

today. Perhaps one of the central questions wonders what it mean to be

human/alive.

First, I don’t recommend you watch Blade Runner as a substitute for this book. While Electric Sheep was the inspiration for Blade Runner the book goes deeper than

the movie with the question of humanity and you do not have to sit through

Harrison Ford’s controlled and stoic acting.

The book starts with the main character, Rick Deckard,

talking to his wife and programing the settings of a “Penfield” to set her mood

and attitude towards life. With this machine you can make someone happy and

willing to please, or moody, or complacent, or satisfied with one’s partner’s

lot in life, and on and on. You can program your mood to whatever you want.

Added to this mechanical mood-setting are androids. Although

they are created in a factory and programed to serve humanity, they have free

will, they have desires and wants, and look to be free from the life they were

slated to live. There are androids that do not want to be servants to humans. Androids

even look like humans when they are cut or killed. They eat and breath and

engage in many ways as humans engage. The more recent incarnation of Battle Star Galactica (2004-2009) embraced

this notion of humanity and machine and plays with the notion well throughout

the series.

What does it mean to be human? On the one hand we have

humans who are living a life of programed emotions and on the other we have

androids who have yearnings and desires to be free. Yet Dick does not stop

there. He introduces us to John Isidore, who is referred to as a “chicken-head”

by others because he has a kind of mental (and maybe physical) defect due to radiation.

He is not treated as fully human and yet he is someone who shows a great amount

of empathy and compassion to humans, androids, and even a spider. There are

other androids who though they have desires to be free do not have empathy or

compassion and rip the legs off of a spider causing Isidore great distress. Without

the empathy, are androids really alive?

Initially Rick Deckard does not feel compassion towards the

androids and questions his humanity when he begins to. To feel for others, to

have compassion might make someone less human? John Isidore has compassion for

all from the begining. Who is fully human?

What does it mean to be human? It is more than just being

flesh and blood. It is more than having desires. It is more than empathy and

compassion. It is all and more or perhaps not. This is what makes Dick’s

writing so good – he does not answer the question. He suggests, he intimates,

he leads the reader to different conclusions, and then lets the reader decide.

If nothing else such a question should lead us to think of our own lives, of

our own relationships, and of the values that are pushed in our society. The

desires that we are fed may not add to our humanity but instead may detract

(like being able to program our mood).

The reader should know that this is not all that Electric Sheep is about. There is the

question of religion and faith, of being alive and seeming alive, and I am sure

other notions to consider. I encourage people to read this book and throughout

to ask themselves what it means to live, to be alive, and to be human.

Monday, March 03, 2014

Traveling Companions

“Life is a journey.”

This trite and overused phrase must be some song lyric or

the beginning of an angst-ridden adolescent poem. It is a cheap and sappy way

to discuss the trials and adventures and difficulties of life and yet it is so

difficult to escape. Many of our great works of literature lift up such a

notion of life being a journey (Dante’s Divine

Comedy, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress,

Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Isben’s Peer Gynt and so on) but they do it

without making the none too subtle and oh so tired statement, “life is a

journey.” I would suggest that Bergman’s film The Silence as a work that also considers this 1980s rock anthem

lyric but in a brilliant and suggestive way that assures you that the syrup of

the phrase will not be offered to you as drink.

If you haven’t seen the film I recommend you watch it, but

with a caveat emptor. It is a little

surreal, a little more worthy of the beret wearing, bongo playing viewer then

some of his other films that I have recently watched. I recommend watching Through a Glass Darkly, and Winter Light, before watching The Silence of which all three are

considered part of Bergman’s “God Trilogy.” You could also read my blog posts

about those movies if you were so inclined.

If The Silence is

about the journey of life we find ourselves at a stopping point offering us the

option to pause and reflect. The beginning and end of the film takes place on a

train (big, big, big metaphor suggesting the journey – seriously, it is a

really, super obvious metaphor… but then I could be reading into it), but the

film primarily takes place in a hotel in a country that is strange for the main

characters. Perhaps another metaphor that calls to be unpacked?

Now before I go any further I want to speak to all of the

elite, snobby film students and scholars out there. Go away. By training I am a

theologian and I will not be discussing the significance of each and every shot

or the meaning of the hot dog dancing in the bun or the idea of the clocks in

every scene. These are important things that merit conversation, but not here.

I have read a number of articles written by you folk and thank you for the

analysis, but they will not be primarily discussed here. If you want that kind

of reflection on Bergman’s movies find a web site that will offer it and get

your kicks there.

For this post I am offering a theological reflection to a provocative

film that I feel is speaking to the notion of the journey of life. Two of the

main characters, Ester and Ana, are committed to their approach to life and the

third, Johan (Ana’s young, circa ten-year-old son) is yet to commit to a way of

living. Ester, the aunt, has chosen a life of scholarship, a life of the mind,

of discipline, of control and of doing what is right. Ana, the mother, has

chosen a life of the experience, a life that is focused on passion, on the joys

of the moment. Johan has yet to choose. As a young boy he is poised between the

two paths; pulled either way.

During their stay at the hotel we see both women fully invested

in their ways of living. Ester writes, translating languages into things she

understands, listens to Bach, and stays in a controlled environment (her hotel

room). Ana goes into the strange world, taking chances, having sexual

encounters, and existing in what many would describe as a free and open

environment. Two different approaches to living.

As I said, I see Johan as pulled between the two. He spends

time in the sensual with his mother as well as in his adventures in the hotel

or in the academic and controlled with his aunt. He has the opportunity to delve

into the sexual at different levels various scenes in the hallways of the

hotel, or he can flee into the controlled and safe space of the known and

understood as he finds in the hotel room with his aunt.

In his writings Søren Kierkegaard has suggested different

approaches to life that seem to connect with the dichotomy offered by the two

women. He discusses the aesthetic which focuses on the joy, the experience of

life. This is not a wasteful hedonism where one’s appetite is the master of

one’s life but is a way of living that looks for life’s pleasures with depth

and value. Then there is the ethical when looks to the rules, the morals, and

the values that may or may not embrace the pleasure of the experience. Some may

say that Kierkegaard is suggesting a hierarchy of living wherein one starts

with the aesthetic and then moves towards the ethical. I don’t want to get into

an argument with Kierkegaardian scholars about this, but I don’t think that is

the case. Rather than suggesting that there is a hierarchy, or developmental

stages to living I would suggest that they are simply different approaches to

life. Some may choose to live the perfect, controlled, rule-based life and

others may choose to follow the beauty and joy of life.

Thus we have Ana with the aesthetic and Ester with the

ethical. Now where is God in all of this? This is, after all, a theological

reflection.

The silence of the movie is the absence of God. The

approaches to living that either sister embraces need not have the presence of

the divine. During the movie we learn that Ester and Ana’s father died well

before the beginning of the film, contributing to some of the tension that the

sisters face. Many scholars who have written on this film suggest that the

father represents God. Thus when the father died it was in actuality God who died

for the two women and for reality of the film. I disagree with this

interpretation. I suggest that when the father died a specific understanding of

God died and the women are trying to find a new sense of life without the

presence of their father (read arcane/outdated/obsolete faith). This is similar

to the wrestling with faith and doubt that I see Thomas struggling with in the

previous movie, Winter Light. The

sisters are following their own paths to living without God and Johan is pulled

between the two.

It seems as if we, the viewers, are faced with an either/or until

the end of the film. Yet there is a turn. Near the end of the film, before saying goodbye to her

nephew, Ester offers Johan a note which has the following words and

translations:

Spirit

Fear (or Anxiety)

Joy

Here is where I believe God speaks. In this note Johan is

offered a third path, one of following the Spirit or the divine. It is a path

that can lead to fear or anxiety because there is a great deal of unknowing in

such a path, in believing and trusting, but there is a deeper joy to be found. This

is the third path and this note breaks the silence of God that pervades

throughout the rest of the movie.

One need not abandon the ethical or the aesthetic to follow

the Spirit but those must serve the following of God. An arcane faith holds to

a God that demands obedience to the rules or a God that is only found in

pleasure. With or without a conception of God either path offers a thin life. Johan

is offered the path of faith in a God that transects the two.

Now you may say that I am reading into the movie and

projecting my own thoughts into the characters of Ana, Ester, and Johan and I

would say that you are right. Well it is my blog and I can do that. And, that

is part of the purpose of good art. Good art invites us in and challenges us to

find the place where our narrative can be understood in the

narrative/idea/experience that is being suggested by the work of art. In this

case I see the narrative of living that is placed before us all and three paths

suggested.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)